Inside at Fleisher/Ollman

- Macy West

- Mar 22, 2025

- 6 min read

It’s hard to put together a group show I like. And no, it’s not because I’m a snob (though there may be other evidence of that.) It’s because curating a room full of objects speaking to each other more often results in cacophony than harmony. Or, not infrequently, the work is wedged into the compartment of a pithy title, which does little besides highlight a particular ideology held by the curator, regardless of what the works themselves have to say on the issue. To be clear, I’m for artwork and exhibitions participating in such commentary, so long as the viewer has space to draw breath, to turn the ideas over in their head, and experience the work as more than just a point in favor of a theme. As curator of the 2019 Venice Biennale Ralph Rugoff points out in his essay You Talking to Me?, “exhibitions are essentially structures for communication, as well as arenas for experience” which is exactly how Inside at Fleisher/Ollman manages to sing out despite the tricky assignment of “group show” (1).

Inside brings together the work of a dozen artists of diverse art educational backgrounds from self-taught, to trained contemporary, to those working in progressive studios. Inside features paintings and ceramics which respond to the work of Becky Suss whose two person show with Carmen Winant, The Present, runs in parallel at the gallery from March 20-May 22, 2025 (2). Suss and Winant explore images, books and objects as vessels that carry private and public histories. Suss works in oil on canvas, constructing intimate compositions of personal objects and domestic spaces as an avenue to discuss the stereotypes of domesticity experienced by generations of American women (3).

Suss’s work prompts a dialog with artists exploring interior spaces and reimagining the still-life tradition. Paintings respond to paintings with little directive other than the flexible title Inside, which operates as an airy canopy under which we experience the nuances of inside worlds. It’s Rugoff’s “arena for experience” and we are under the refreshing shade of Suss’s paintings. We want to linger, to look closer. There is space for introspection, to treasure our own nostalgic items, and examine how we construct our domestic spaces to mirror our internal worlds.

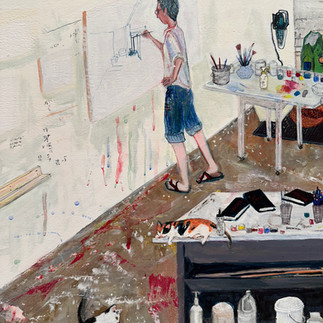

Rugoff points out that, like packaging for consumer goods or the architecture of the buildings we inhabit, a group show operates to shape our perception and behavior with regard to the object or environment. But it should also offer loopholes and surprising escape hatches. At Fleisher/Ollman, you pass through The Present to the second room Inside which feels conceptually and physically like being asked to stay. You cross the threshold only to encounter a choose-your-own-adventure in and out of Kate Abercrobie’s Catch-all, a playfully rendered drawer of odds and ends. You peer into Sarah McEneaney’s studio from a dreamy vantage, which is somehow both too far away and possessing the clarity to see every detail including the artist’s notes scribbled on the wall. Depending on the path you walked, you may conclude your trip, like me, with the magical encounter of Olivia Jia’s Night Reading. It’s a tiny painting of an open book in twilight colors that feels somehow more real and present than the books scattered about my apartment as I write. It’s a beautiful way to close your adventure as you remember the first Becky Suss painting in The Present where we started. One room over was Suss’s painting of another open book, Jim’s Book, which has a different kind of presence, one less specific but maybe appropriately open-ended as a starting point for Inside.

If I am going to adhere strictly to Rugoff’s definition, I must also discuss the exhibition as a “structure for communication,” which honestly is harder for me to do. I’ll share my thoughts, but first must clarify that these come to me only now, two days after seeing the show. In many ways, Inside’s triumph as an arena for experience is to its detriment when it comes to building a structure for communication, a space to explore unanswered questions. The show (and the viewer experiencing it) is so intoxicated by the paintings that it's hard to exit the delightful bubble of personal introspection, and close inspection, peering into and communing with the paintings. The show does not immediately spark interpersonal communication when you're Inside. Pun intended. In particular, there is a level of, if not sameness, certainly repetitiveness to some of these super tightly built paintings: velvety smooth surfaces, extreme precision and attention to detail and perfectly taped edges are hallmarks of paintings, by not only Becky Suss, but also many others including Sarah Pater, Olivia Jia, and Ann Toebbe. Even the works that follow more expressive modes of representation are so specific in their moment and mood that you can quite contentedly exist as observer, float through the arena of experience, and, though you relish every minute, go out the door without a question.

I say “you”, and fault the exhibition while being fully aware that this could simply be a result of my own disposition as an observer and thinker first. I’m slow when it comes to responding. But if that was my experience it's not improbable that a curator could get similarly lost in a room full of these beautiful paintings and forget to leave the door open to improvisation and to the uncertainty of what we each bring in from the outside. Maybe it's a both and situation: partially me, partially the curation of those works in the room that made it difficult for me to exit the coziness of these private spaces with a sense of the cultural implications of the work. Maybe the paintings were too beautiful?

I will pick up on something I noted earlier that has been lurking since I left the show: There is space for introspection, to treasure our own nostalgic items, and examine how we construct our domestic spaces to mirror our internal worlds. While introspection and nostalgia may have dulled my ability to communicate at the show, I think the show does have a power to linger in your mind, especially if you are someone like me who revisits photos of details captured while in the exhibition. There is a psychological uneasiness to seeing these intimate spaces and objects detached from their maker and a similar uncertainty about how my own domestic space might reveal my psychological world. Reflecting on my own interior space, now home, now in my studio, now writing, and now relooking, I notice my tendency to order and decorate spaces to quiet my own thoughts. If I were to paint my space it has the capacity to reveal those things about my interior world. Without my presence as mediator, that painting could give an uncanny self-portrait of how I think, feel, and live when I’m alone. Anyone can see these personal objects and spaces and draw their own conclusions that recreate the maker's psychology.

Then I start asking questions. I want to re-examine the work more closely. Like maybe Jia’s mesmerizing painting left me slightly unsettled in its hyperrealness. I mentioned how it felt more real than my own physical books. What does that mean for our relationship to images and how we define materiality, reality, and perceptual experience? Maybe when I relook at Sarah McEneaney’s studio painting, I start to wonder how I can see such detail from such an unlikely vantage. The mismatch is disconcerting. Julian Kent’s Still Life for Birdie Lusch is, at first glance, charming and whimsical. On second look, there’s a surreality to the way the objects relate to one another, like they are not from the same space. I say all this not to mean that what looks like a beautiful show actually has an eerily dark secret, but to underscore how Inside begins to reveal the intertwined nature of our psychological and material spaces and what it means to share these spaces. It’s where my mind goes once I break the spell cast by John Joseph Mitchell’s Still Life with a Decoy Duck and Mandarins, another painting which draws you into its timeless place.

There is space for introspection, to treasure our own nostalgic items, and examine how we construct our domestic spaces to mirror our internal worlds; that’s where we were before we swam down my stream-of-consciousness curiosity about the show. It was worth the journey, for me at least, for showing the exhibition’s “structure of communication.” As Rugoff says toward the end of the same essay:

"…such an exhibition encourages me to actively seek out uncertainty, rather than simply remaining unsure. And it is precisely when we are unsure of something that our curiosity is aroused, and that we then tend to regard it more closely, consider it more carefully, and in the end, experience it more intensely."

Inside starts to take me there. Once I leave the gallery. Once I have time to sit with my thoughts and scroll back through my camera roll of all the details I photographed. But it’s hard when you're in the room.

(1) Rugoff, Ralph “You Talking To Me? On Curating Group Shows that Give You a Chance to Join the Group” in What Makes a Great Exhibition, Paula Marincola (Ed.), Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative, Philadelphia (2006), p. 45-49.

(2) Fleisher/Ollman, "Exhibitions," https://www.fleisher-ollmangallery.com/exhibitions

(3) Jack Shainman, "Becky Suss," https://jackshainman.com/artists/becky_suss